Last modified: Jan 31 2026 at 10:09 PM • 4 mins read

Gradient Descent

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Visualizing Gradient Descent

- How Gradient Descent Works

- Understanding the Derivative

- Full Gradient Descent for Logistic Regression

- Understanding Notation: $d$ vs $\partial$

- Implementation Summary

- Key Takeaways

Introduction

Now that we have defined the cost function $J(w, b)$, we need an algorithm to minimize it and learn the optimal parameters $w$ and $b$. This algorithm is called gradient descent.

Recap:

\[J(w, b) = -\frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[y^{(i)} \log(\hat{y}^{(i)}) + (1-y^{(i)}) \log(1-\hat{y}^{(i)})\right]\]Goal: Find $w$ and $b$ that minimize $J(w, b)$.

Visualizing Gradient Descent

The Cost Function Surface

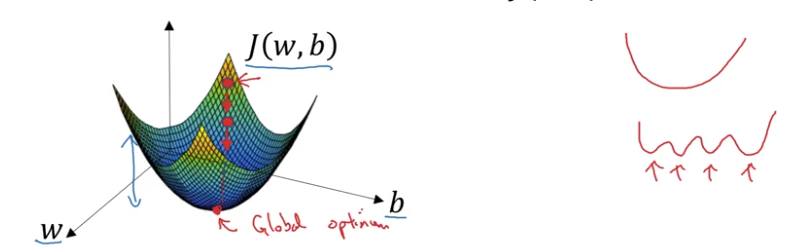

Imagine the cost function as a 3D surface:

- Horizontal axes: Parameters $w$ and $b$

- (In practice, $w$ can be high-dimensional, but we’ll use 1D for visualization)

- Vertical axis: Value of $J(w, b)$

- Surface height: The cost at each point

Convex vs Non-Convex Functions

Convex function (our logistic regression cost):

- Single “bowl” shape

- One global minimum

- No local minima

Non-convex function:

- Multiple “hills and valleys”

- Many local minima

- Harder to optimize

Why this matters: Our cost function $J(w, b)$ is convex, which is why we chose this particular function. This guarantees we can find the global minimum.

How Gradient Descent Works

The Algorithm

Step 1: Initialize

- Start with initial values for $w$ and $b$ (usually $w = 0$, $b = 0$)

- Because the function is convex, initialization doesn’t matter much

Step 2: Repeat until convergence

- Take a step in the steepest downhill direction

- Move toward lower cost

- Each step brings us closer to the minimum

Step 3: Converge

- Eventually reach the global minimum (or very close to it)

Mathematical Update Rule

For a simplified 1D case (just parameter $w$):

\[w := w - \alpha \frac{dJ(w)}{dw}\]Where:

- $:=$ means “update” or “assign”

- $\alpha$ is the learning rate (controls step size)

- $\frac{dJ(w)}{dw}$ is the derivative (slope of the cost function)

Code convention: We use dw as the variable name for $\frac{dJ(w)}{dw}$

w = w - alpha * dw

Understanding the Derivative

What is a Derivative?

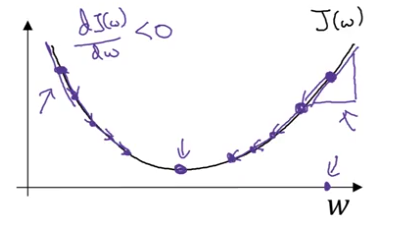

The derivative $\frac{dJ(w)}{dw}$ represents the slope of the cost function at the current point.

Intuition:

- Slope = height / width of the tangent line

- Tells us which direction is “downhill”

- Tells us how steep the slope is

How the Update Works

Case 1: Positive slope (derivative > 0)

- If $w$ is to the right of the minimum

- Derivative is positive

- $w := w - \alpha \times (\text{positive}) = w - \text{positive}$

- $w$ decreases → moves left toward minimum

Case 2: Negative slope (derivative < 0)

- If $w$ is to the left of the minimum

- Derivative is negative

- $w := w - \alpha \times (\text{negative}) = w + \text{positive}$

- $w$ increases → moves right toward minimum

Result: Regardless of where you start, gradient descent moves you toward the minimum.

Full Gradient Descent for Logistic Regression

For logistic regression with parameters $w$ and $b$:

Update rules:

\[w := w - \alpha \frac{\partial J(w,b)}{\partial w}\] \[b := b - \alpha \frac{\partial J(w,b)}{\partial b}\]Code convention:

w = w - alpha * dw # dw represents ∂J/∂w

b = b - alpha * db # db represents ∂J/∂b

Understanding Notation: $d$ vs $\partial$

The Confusing Calculus Notation

Single variable (one parameter):

- Use regular $d$: $\frac{dJ(w)}{dw}$

Multiple variables (two or more parameters):

- Use partial derivative $\partial$: $\frac{\partial J(w,b)}{\partial w}$

Important: They mean almost the same thing! Both represent the slope with respect to one variable.

Why This Notation Exists

The rule is:

- $J(w)$ → use $\frac{d}{dw}$ (ordinary derivative)

- $J(w, b)$ → use $\frac{\partial}{\partial w}$ (partial derivative)

Don’t worry too much about this distinction - both measure the slope in one direction.

Implementation Summary

In code, we use these conventions:

| Mathematical Notation | Code Variable | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| $\frac{\partial J(w,b)}{\partial w}$ | dw | Amount to update $w$ |

| $\frac{\partial J(w,b)}{\partial b}$ | db | Amount to update $b$ |

| $\alpha$ | alpha or learning_rate | Step size |

Update step:

# Compute gradients (we'll learn how in next lessons)

dw = compute_gradient_w(...)

db = compute_gradient_b(...)

# Update parameters

w = w - alpha * dw

b = b - alpha * db

Key Takeaways

- Gradient descent finds the minimum of the cost function

- The derivative (slope) tells us which direction to move

- The learning rate $\alpha$ controls how big each step is

- We repeat the update until convergence

- Because $J(w,b)$ is convex, we always reach the global minimum