Last modified: Jan 31 2026 at 10:09 PM • 6 mins read

Vanishing / Exploding Gradients

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The Problem Setup

- Mathematical Derivation

- Case 1: Exploding Gradients

- Case 2: Vanishing Gradients

- General Intuition

- Real-World Context

- Impact on Training

- Visualization: The Critical Region

- Why This Matters

- The Solution Preview

- Key Takeaways

Introduction

One of the most challenging problems when training very deep neural networks is the phenomenon of vanishing and exploding gradients. During training, your derivatives (gradients) can become either:

- Exponentially large (exploding) → Training becomes unstable

- Exponentially small (vanishing) → Learning becomes impossibly slow

This lesson explores why this happens and introduces how careful weight initialization can significantly reduce this problem.

The Problem Setup

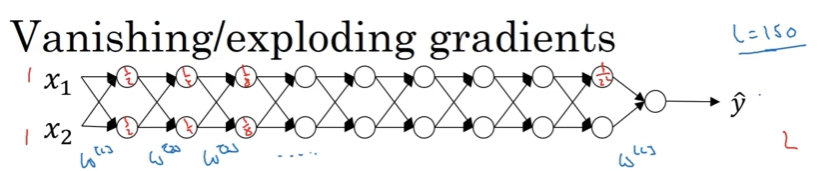

Consider a very deep neural network with $L$ layers:

Architecture:

- Input: $X$

- Hidden layers: $L-1$ layers

- Output: $\hat{Y}$

- Parameters: $W^{[1]}, W^{[2]}, W^{[3]}, \ldots, W^{[L]}$ and $b^{[1]}, b^{[2]}, \ldots, b^{[L]}$

Simplifying Assumptions (for illustration):

- Use linear activation function: $g(z) = z$ (no nonlinearity)

- Set all biases to zero: $b^{[l]} = 0$ for all layers

- Each layer has 2 hidden units (though this generalizes to any size)

Note: These assumptions are unrealistic for real networks but help us understand the mathematical behavior clearly.

Mathematical Derivation

Forward Propagation with Linear Activations

With our simplifying assumptions, let’s trace what happens:

Layer 1:

\[Z^{[1]} = W^{[1]}X + b^{[1]} = W^{[1]}X \quad \text{(since } b^{[1]} = 0\text{)}\] \[A^{[1]} = g(Z^{[1]}) = Z^{[1]} = W^{[1]}X \quad \text{(since } g(z) = z\text{)}\]Layer 2:

\[Z^{[2]} = W^{[2]}A^{[1]} = W^{[2]}W^{[1]}X\] \[A^{[2]} = Z^{[2]} = W^{[2]}W^{[1]}X\]Continuing this pattern through all layers:

\[\hat{Y} = A^{[L]} = W^{[L]} \cdot W^{[L-1]} \cdot W^{[L-2]} \cdots W^{[3]} \cdot W^{[2]} \cdot W^{[1]} \cdot X\]Key Insight: The output is the product of all weight matrices multiplied by the input!

Case 1: Exploding Gradients

Scenario: Weights Slightly Larger Than Identity

Assume each weight matrix is slightly larger than the identity matrix:

\[W^{[l]} = \begin{bmatrix} 1.5 & 0 \\ 0 & 1.5 \end{bmatrix} = 1.5 \cdot I\]Where $I$ is the identity matrix.

The Exponential Growth

Since each layer multiplies by 1.5:

\[\hat{Y} \approx \left(1.5 \cdot I\right)^{L-1} \cdot X = 1.5^{L-1} \cdot X\]Effect on Activations:

For a deep network with $L = 150$ layers:

\[1.5^{149} \approx 3.7 \times 10^{26}\]This is astronomically large!

Example - Activation Growth:

| Layer | Activation Magnitude | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Layer 1 | $1.5$ | $1.5^1$ |

| Layer 2 | $2.25$ | $1.5^2$ |

| Layer 3 | $3.375$ | $1.5^3$ |

| Layer 10 | $\approx 57.7$ | $1.5^{10}$ |

| Layer 50 | $\approx 6.4 \times 10^8$ | $1.5^{50}$ |

| Layer 150 | $\approx 3.7 \times 10^{26}$ | $1.5^{150}$ |

The Problem

- Activations explode exponentially with network depth

- Gradients also explode (by similar reasoning during backpropagation)

- Training becomes numerically unstable

- Can cause NaN (Not a Number) or Inf values

Case 2: Vanishing Gradients

Scenario: Weights Slightly Smaller Than Identity

Now assume each weight matrix is slightly smaller than the identity:

\[W^{[l]} = \begin{bmatrix} 0.5 & 0 \\ 0 & 0.5 \end{bmatrix} = 0.5 \cdot I\]The Exponential Decay

Since each layer multiplies by 0.5:

\[\hat{Y} \approx \left(0.5 \cdot I\right)^{L-1} \cdot X = 0.5^{L-1} \cdot X\]Effect on Activations:

If input $X = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \ 1 \end{bmatrix}$:

| Layer | Activation Values | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Layer 1 | $[0.5, 0.5]$ | $0.5^1$ |

| Layer 2 | $[0.25, 0.25]$ | $0.5^2$ |

| Layer 3 | $[0.125, 0.125]$ | $0.5^3$ |

| Layer 10 | $[9.8 \times 10^{-4}, 9.8 \times 10^{-4}]$ | $0.5^{10}$ |

| Layer 50 | $[8.9 \times 10^{-16}, 8.9 \times 10^{-16}]$ | $0.5^{50}$ |

| Layer 150 | $[7.0 \times 10^{-46}, 7.0 \times 10^{-46}]$ | $0.5^{150}$ |

The Problem

- Activations vanish exponentially with network depth

- Gradients also vanish during backpropagation

- Gradient descent takes tiny steps

- Learning becomes impossibly slow

- Early layers learn almost nothing

General Intuition

The key insight applies beyond our simplified example:

Exploding Case

Condition: $W^{[l]} > I$ (weights slightly larger than identity)

\[W^{[l]} \approx \lambda I \quad \text{where } \lambda > 1\]Result:

\[\text{Activations} \propto \lambda^L \rightarrow \infty \quad \text{as } L \rightarrow \infty\]Similarly for gradients: They grow exponentially during backpropagation.

Vanishing Case

Condition: $W^{[l]} < I$ (weights slightly smaller than identity)

\[W^{[l]} \approx \lambda I \quad \text{where } \lambda < 1\]Result:

\[\text{Activations} \propto \lambda^L \rightarrow 0 \quad \text{as } L \rightarrow \infty\]Similarly for gradients: They shrink exponentially during backpropagation.

Real-World Context

Modern Deep Networks

Example - ResNet: Microsoft achieved breakthrough results with a 152-layer network (ResNet-152).

With $L = 152$:

- If $\lambda = 1.1$: Activations scale by $1.1^{152} \approx 2.3 \times 10^6$

- If $\lambda = 0.9$: Activations scale by $0.9^{152} \approx 7.3 \times 10^{-8}$

Even small deviations from 1.0 cause massive problems in very deep networks!

Impact on Training

Exploding Gradients

| Symptom | Effect |

|---|---|

| Very large gradient updates | Parameters jump around wildly |

| Loss becomes NaN or Inf | Training crashes |

| Numerical overflow | Computations fail |

| Unstable training | Cannot converge |

Gradient Descent Behavior: Makes huge, erratic steps that overshoot the minimum.

Vanishing Gradients

| Symptom | Effect |

|---|---|

| Extremely small gradient updates | Parameters barely change |

| Loss plateaus early | Appears “stuck” |

| Early layers don’t learn | Only last few layers train |

| Very slow convergence | Training takes forever |

Gradient Descent Behavior: Takes microscopic steps, making negligible progress.

# Illustration of gradient magnitudes in a 150-layer network

import numpy as np

# Exploding gradients

lambda_exploding = 1.1

gradient_scale_exploding = lambda_exploding ** 150

print(f"Exploding: Gradient scaled by {gradient_scale_exploding:.2e}")

# Vanishing gradients

lambda_vanishing = 0.9

gradient_scale_vanishing = lambda_vanishing ** 150

print(f"Vanishing: Gradient scaled by {gradient_scale_vanishing:.2e}")

# Output:

# Exploding: Gradient scaled by 2.28e+06

# Vanishing: Gradient scaled by 7.30e-08

Visualization: The Critical Region

Gradient Behavior as Function of Weight Scaling:

|

| ↗ Exploding (λ > 1)

| /

| /

1.0 |---●------ Critical Point (λ = 1)

| \

| \

| ↘ Vanishing (λ < 1)

|

+------------------

Weight Scale (λ)

The Challenge: Keeping weights in the narrow “stable” region near $\lambda = 1$ throughout all layers.

Why This Matters

For very deep networks:

- Depth amplifies the problem: Each layer compounds the effect

- Exponential behavior: Small weight imbalances lead to huge differences

- Training becomes impractical: Without solutions, deep networks can’t be trained effectively

The Solution Preview

The next lesson covers weight initialization strategies that help keep weights in the stable region, including:

- Xavier/Glorot initialization (for tanh/sigmoid)

- He initialization (for ReLU)

- Variance scaling based on layer dimensions

These techniques set initial weights to prevent gradients from exploding or vanishing from the start.

Key Takeaways

The Problem: In very deep networks, gradients can become exponentially large (exploding) or exponentially small (vanishing)

Root Cause: Repeated multiplication of weight matrices during forward/backward propagation

- Mathematical Pattern:

- Weights $> 1$ → Exponential growth → Exploding gradients

- Weights $< 1$ → Exponential decay → Vanishing gradients

- Impact on Training:

- Exploding: Unstable training, NaN values, divergence

- Vanishing: Extremely slow learning, early layers don’t train

- Depth Matters: The effect scales with $\lambda^L$ where $L$ is the number of layers

- Modern networks: $L = 150+$ layers make this critical

- Solution: Careful weight initialization (covered in the next lesson) can significantly mitigate this problem by keeping weights near the stable region