Last modified: Jan 31 2026 at 10:09 PM • 7 mins read

Regularization

Table of contents

- Introduction

- L2 Regularization for Logistic Regression

- L1 vs L2 Regularization

- The Regularization Parameter $\lambda$

- L2 Regularization for Neural Networks

- Implementing Regularized Gradient Descent

- Why It’s Called “Weight Decay”

- Implementation Summary

- Key Takeaways

Introduction

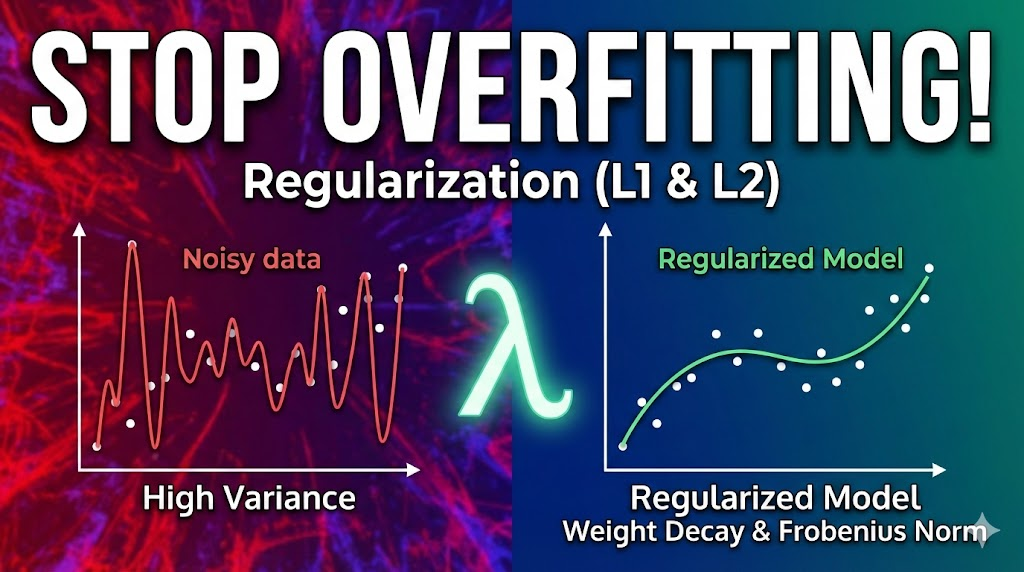

When you diagnose that your neural network has a high variance problem (overfitting), regularization should be one of the first techniques you try. While getting more training data is also effective, it’s often:

- Expensive to collect

- Time-consuming to acquire

- Sometimes impossible to obtain

Regularization is your most practical weapon against overfitting, and it works by adding a penalty for model complexity.

L2 Regularization for Logistic Regression

Standard Logistic Regression Cost Function

Recall the standard cost function for logistic regression:

\[J(w, b) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathcal{L}(\hat{y}^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\]Where:

- $w \in \mathbb{R}^{n_x}$ is the weight vector (parameter vector)

- $b \in \mathbb{R}$ is the bias (scalar)

- $m$ is the number of training examples

- $\mathcal{L}$ is the loss function for individual predictions

Adding L2 Regularization

To add L2 regularization, modify the cost function:

\[J(w, b) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathcal{L}(\hat{y}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) + \frac{\lambda}{2m} \|w\|_2^2\]Where the regularization term is:

\[\frac{\lambda}{2m} \|w\|_2^2 = \frac{\lambda}{2m} \sum_{j=1}^{n_x} w_j^2 = \frac{\lambda}{2m} w^T w\]Components:

- $\lambda$ is the regularization parameter (hyperparameter to tune)

- $|w|_2^2$ is the squared L2 norm (Euclidean norm) of $w$

- This is called L2 regularization because it uses the L2 norm

Why Only Regularize $w$, Not $b$?

Short answer: $b$ is just one parameter, while $w$ is high-dimensional.

Detailed explanation:

| Parameter | Dimensionality | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| $w$ | $n_x$-dimensional vector | Contains most parameters |

| $b$ | Single scalar | Just 1 parameter |

Reasoning:

- In high-variance problems, $w$ has many parameters (potentially thousands or millions)

- Adding $\frac{\lambda}{2m} b^2$ would have negligible impact

- In practice, regularizing only $w$ works just as well

You can include $b$ if you want, but it’s not standard practice and won’t make much difference.

L1 vs L2 Regularization

L1 Regularization (Less Common)

\[J(w, b) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathcal{L}(\hat{y}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) + \frac{\lambda}{m} \|w\|_1\]Where:

\[\|w\|_1 = \sum_{j=1}^{n_x} |w_j|\]Properties of L1 regularization:

- Makes $w$ sparse (many weights become exactly zero)

- Can be used for feature selection (non-zero weights indicate important features)

- Helps with model compression (fewer non-zero parameters to store)

In practice: L1 regularization is used much less often than L2.

Why L1 isn’t popular:

- Model compression benefit is marginal

- Doesn’t prevent overfitting as effectively as L2

- Creates computational challenges (non-differentiable at zero)

L2 Regularization (Most Common)

\[J(w, b) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathcal{L}(\hat{y}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) + \frac{\lambda}{2m} \|w\|_2^2\]Why L2 is preferred:

- ✅ More effective at preventing overfitting

- ✅ Smooth, differentiable everywhere

- ✅ Works well with gradient descent

- ✅ Strong theoretical foundations

Comparison Table

| Aspect | L1 Regularization | L2 Regularization |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | $\frac{\lambda}{m} \sum \vert w_j \vert$ | $\frac{\lambda}{2m} \sum w_j^2$ |

| Result | Sparse weights (many zeros) | Small but non-zero weights |

| Use case | Feature selection, compression | Preventing overfitting |

| Popularity | Less common | Most common |

| Optimization | Non-smooth | Smooth, easy to optimize |

The Regularization Parameter $\lambda$

What is $\lambda$?

Definition: $\lambda$ (lambda) controls the tradeoff between:

- Fitting the training data well (low training error)

- Keeping weights small (preventing overfitting)

How to Choose $\lambda$

Process: Use your dev set (hold-out cross-validation) to tune $\lambda$

Strategy:

- Try various values: $\lambda \in {0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100}$

- Train model with each $\lambda$

- Evaluate on dev set

- Choose $\lambda$ that gives best dev set performance

Effect of Different $\lambda$ Values

| $\lambda$ Value | Effect on Weights | Training Error | Dev Error | Problem |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $\lambda = 0$ | No regularization | Very low | High | Overfitting |

| $\lambda$ too small | Weak regularization | Low | High | Still overfitting |

| $\lambda$ optimal | Balanced | Low | Low | ✅ Just right |

| $\lambda$ too large | Weights too small | High | High | Underfitting |

Python Implementation Note

⚠️ Important: lambda is a reserved keyword in Python!

Solution: Use lambd (without the ‘a’) in code

# Correct Python syntax

lambd = 0.01 # Regularization parameter

# Wrong - will cause syntax error

lambda = 0.01 # Reserved keyword!

L2 Regularization for Neural Networks

Neural Network Cost Function

For a neural network with $L$ layers:

Standard cost function:

\[J(W^{[1]}, b^{[1]}, \ldots, W^{[L]}, b^{[L]}) = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathcal{L}(\hat{y}^{(i)}, y^{(i)})\]With L2 regularization:

\[J = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathcal{L}(\hat{y}^{(i)}, y^{(i)}) + \frac{\lambda}{2m} \sum_{l=1}^{L} \|W^{[l]}\|_F^2\]The Frobenius Norm

The regularization term uses the Frobenius norm of weight matrices:

\[\|W^{[l]}\|_F^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n^{[l]}} \sum_{j=1}^{n^{[l-1]}} (W_{ij}^{[l]})^2\]Where:

- $W^{[l]}$ is the weight matrix for layer $l$

- $W^{[l]} \in \mathbb{R}^{n^{[l]} \times n^{[l-1]}}$

- $n^{[l]}$ = number of units in layer $l$

- $n^{[l-1]}$ = number of units in layer $l-1$

Why “Frobenius norm”?

For arcane linear algebra reasons, the sum of squared elements of a matrix is called the Frobenius norm, not the L2 norm of a matrix. It’s denoted with subscript $F$: $|\cdot|_F$

Intuition: It’s just the sum of all squared elements in the matrix—nothing mysterious!

Complete Regularization Term

Summing across all layers:

\[\text{Regularization term} = \frac{\lambda}{2m} \sum_{l=1}^{L} \sum_{i=1}^{n^{[l]}} \sum_{j=1}^{n^{[l-1]}} (W_{ij}^{[l]})^2\]Implementing Regularized Gradient Descent

Without Regularization (Standard Update)

Step 1: Compute gradient using backpropagation

\[dW^{[l]} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial W^{[l]}} \quad \text{(from backprop)}\]Step 2: Update weights

\[W^{[l]} := W^{[l]} - \alpha \cdot dW^{[l]}\]With L2 Regularization (Modified Update)

Step 1: Compute gradient with regularization term

\[dW^{[l]} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial W^{[l]}} + \frac{\lambda}{m} W^{[l]}\]Step 2: Update weights (same formula as before)

\[W^{[l]} := W^{[l]} - \alpha \cdot dW^{[l]}\]Expanding the Update Rule

Substituting the modified gradient:

\[W^{[l]} := W^{[l]} - \alpha \left( \frac{\partial J_{\text{original}}}{\partial W^{[l]}} + \frac{\lambda}{m} W^{[l]} \right)\]Rearranging:

\[W^{[l]} := W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{\lambda}{m} W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{\partial J_{\text{original}}}{\partial W^{[l]}}\]Factoring out $W^{[l]}$:

\[W^{[l]} := \left(1 - \alpha \frac{\lambda}{m}\right) W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{\partial J_{\text{original}}}{\partial W^{[l]}}\]Why It’s Called “Weight Decay”

The Key Observation

Looking at the factored form:

\[W^{[l]} := \underbrace{\left(1 - \alpha \frac{\lambda}{m}\right)}_{\text{Decay factor}} W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{\partial J_{\text{original}}}{\partial W^{[l]}}\]The decay factor: $(1 - \alpha \frac{\lambda}{m}) < 1$

What’s Happening

Before applying the gradient update, weights are multiplied by a number slightly less than 1:

| Component | Value | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Learning rate | $\alpha$ = 0.01 | Small number |

| Regularization | $\lambda$ = 0.01 | Small number |

| Training size | $m$ = 10,000 | Large number |

| Decay factor | $1 - \frac{0.01 \times 0.01}{10000} \approx 0.999999$ | Slightly less than 1 |

Example with typical values:

- $\alpha = 0.01$

- $\lambda = 0.01$

- $m = 10,000$

- Decay factor = $1 - \frac{0.01 \times 0.01}{10,000} = 0.999999$

Each iteration, weights are multiplied by 0.999999 before the gradient update—they decay slightly!

The Two-Step Process

Step 1 (Weight Decay): Shrink weights slightly

\[W^{[l]} := 0.9999 \cdot W^{[l]}\]Step 2 (Gradient Update): Apply gradient descent as usual

\[W^{[l]} := W^{[l]} - \alpha \frac{\partial J}{\partial W^{[l]}}\]This is why L2 regularization is also called “weight decay”—it literally decays (shrinks) the weights on each iteration!

Implementation Summary

Logistic Regression

# Cost function with L2 regularization

J = (1/m) * np.sum(losses) + (lambd/(2*m)) * np.sum(w**2)

# Gradient with regularization

dw = (1/m) * np.dot(X, (A - Y).T) + (lambd/m) * w

# Update

w = w - alpha * dw

b = b - alpha * db

Neural Network

# Cost function with L2 regularization

L2_regularization = 0

for l in range(1, L+1):

L2_regularization += np.sum(np.square(W[l]))

J = (1/m) * np.sum(losses) + (lambd/(2*m)) * L2_regularization

# Gradient for layer l

dW[l] = (1/m) * np.dot(dZ[l], A[l-1].T) + (lambd/m) * W[l]

# Update

W[l] = W[l] - alpha * dW[l]

b[l] = b[l] - alpha * db[l]

Key Code Pattern

The pattern for regularized gradient descent is always:

# 1. Compute gradient from backprop

dW = backprop_gradient(...)

# 2. Add regularization term

dW = dW + (lambd/m) * W

# 3. Update weights

W = W - alpha * dW

Key Takeaways

- First line of defense: Regularization should be your first try when facing overfitting

- L2 most common: L2 regularization is far more popular than L1 in practice

- Regularization term: Add $\frac{\lambda}{2m} |W|^2$ to cost function

- Lambda is hyperparameter: Tune $\lambda$ using dev set, typical values: 0.01 to 10

- Don’t regularize bias: Only regularize $w$ or $W$, not $b$ (negligible impact)

- Frobenius norm: For matrices, use squared Frobenius norm = sum of all squared elements

- Modified gradient: Add $\frac{\lambda}{m} W$ to gradient from backprop

- Weight decay: L2 regularization shrinks weights by factor $(1 - \alpha\frac{\lambda}{m})$

- Python keyword: Use

lambdin code, notlambda - Sparse vs small: L1 makes weights sparse (zeros), L2 makes weights small

- All layers: Apply regularization to all weight matrices in neural network

- Simple implementation: Just modify gradient computation and cost function

- Tradeoff tuning: $\lambda$ controls training fit vs weight size tradeoff

- Computational cost: Minimal—just one extra term in gradient